INTRODUCTION

The CDC definition for lead toxicity has been progressively lowered over the past 50 years to reflect evidence that harm exists at the lowest detectable levels. Despite increased screening and an evolving awareness surrounding lead exposure, the development of treatments and guidelines for exposed patients has slowed dramatically since the early 2000s. Most guidelines recommend against using chelation treatment for BLLs <45 µg/dL, yet the current reference level is 3.5 µg/dL, leaving a substantial treatment gap for patients with BLLs between 3.5 and 45 µg/dL.

The treatment guidelines rely on findings from the Treatment of Lead-Exposed Children (TLC) randomized controlled trial. The TLC trial studied the effects of succimer (DMSA) chelation on IQ in children with BLLs 20-44 µg/dL. The investigators showed that although DMSA lowered BLLs short-term, this effect was not sustained, and no cognitive benefit was detected after 3 years.

The investigators concluded that chelation therapy was not indicated for children with BLLs <45 µg/dL, and suggested that further efforts should shift towards primary prevention and away from finding and treating patients.

In the years that followed, these suggestions were fundamental in shaping U.S. environmental health policy, redirecting responsibilities away from treatment by physicians and towards housing and environmental efforts by federal agencies.

While this shift has been beneficial in some ways, efforts have largely failed at preventing children from being exposed to lead hazards. As a result, many children continue to be exposed to lead, and are left without medical options. Finding and treating children who have been exposed to lead is necessary until lead hazards have been fully addressed.

TLC was conducted prior to widespread adherence to CONSORT and ICMJE standards. Given its continued influence, we believed a re-examination of the TLC trial was warranted. We re-examined the trial’s background, methodology, limitations and impact on shaping current U.S. environmental health policy and clinical treatment guidelines over the last twenty five years.

Environmental Exposure Uncontrolled. Most notably, the trial failed to prevent ongoing environmental exposure in participants. Chelating children while they continue to be exposed to lead has always been contraindicated. TLC provided a home cleaning pre-randomization but lead dust levels remained above federal standards. The house cleaning was designed to suppress lead dust in children’s homes for roughly six months during therapy. The primary principle behind chelation, and lead interventions in general, is removing long-term sources of exposure. It’s ironic that the trial has been used to steer policy away from medical treatment and towards primary prevention, when it failed to prevent ongoing exposure in its own participants.

Mineral Status Unmonitored. The TLC children were at high baseline risk for mineral deficiency given that most of them lived in poverty. The treatment group was at greater risk of depletion due to succimer’s ability to chelate other minerals during treatment. To address this possibility, children were given multivitamins empirically, but were not monitored for mineral deficiency beyond ferritin values at randomization. This lack of monitoring introduced the potential for effect modification and confounding on the primary neurodevelopmental and secondary growth outcomes. While succimer is less likely than EDTA to cause mineral depletion, the preclinical trials that showed this were done over 5-day courses, not 26 days. It’s plausible that zinc, iron, or copper deficiency may have played a role in the reduced linear growth noted in the treatment group. Identifying and addressing mineral deficiencies, if present, is generally always included in a comprehensive treatment plan when treating children with lead exposure.

Ferritin Reporting. The trial measured baseline ferritin in its participants but did not report baseline ferritin status of randomized groups among lab values in all but one publication—describing the effect of chelation on growth—published in 2006. In that instance, they reported ferritin as the arithmetic mean. To explain their handling of mineral status (iron in particular) they published a paper which included analysis on a convenience sample of enrolled (but not necessarily randomized) participants, comparing arithmetic mean ferritin with that of NHANES III subjects. They concluded that TLC children with high BLLs had no difference in iron status compared to NHANES III children with lower BLLs, and thus, there was no need to treat or test for iron deficiency with BLLs 20-44 µg/dL.

Arithmetic vs. Geometric Mean Ferritin. Using the arithmetic mean value for ferritin distribution is generally not the best measure of central tendency for skewed distributions. Ferritin, especially in children, is characteristically right skewed and should be analyzed by geometric mean as the best measure of central tendency. Our analyses of NHANES 1998-2002 revealed an arithmetic mean of 28.14 ng/mL for children ages 1-5 across all races, and a median of 22 ng/mL—leaving half of all children in a range considered physiologically deficient (~20 ng/mL). Ferritin analyses should be adjusted with CRP values, since inflammation can increase ferritin levels even in iron deficient states. The analyses we performed are consistent with TLC’s, showing little difference in ferritin among different BLL quartiles. However, our interpretation differs in that we believe on average most children are at risk of iron deficiency. Iron deficiency increases lead exposure and absorption, so all children who are at risk of exposure should be screened (using CRP & ferritin) and treated for iron deficiency.

Lead-Contaminated Vitamins. Toward the end of the trial, a batch of multivitamins given to participants was found to be contaminated with lead, with 628 of 780 participants potentially exposed. The recall was discussed separately, noting that adherence was variable; of the exposed, 571 were analyzed for BLLs to assess the incident. The authors note that 149 siblings were also exposed, and all but one trial site encouraged sharing of multivitamins with siblings and family. Their interpretation was that no dose-response effect was found, so nothing more was done. The primary NEJM publication mentions the incident in one sentence, citing the ancillary article; the five-year follow-up does not mention it. While the incident likely had little effect on the primary outcome, the lack of rigor and candor in reporting and analysis raises questions about overall trial conduct.

Treatment Endpoint and Power. Our opinion contrasts with the TLC’s interpretation that another treatment protocol would unlikely yield different results. The treatment endpoint of 15 µg/dL was insufficient given current understanding of relationships between IQ and BLL. Chelating to lower levels, ideally less than 10 µg/dL, would have been much more likely to result in a detectable IQ increase.

Conclusion. These factors, combined, make interpretation of the TLC trial results difficult. Ultimately, the TLC trial showed that succimer chelation is not a replacement for reducing environmental exposure, nor a magic bullet for lead’s persistent cognitive damage. It illustrated how a single randomized controlled trial can shape national policy for decades, redirecting efforts from identifying and refining clinical treatment toward an almost exclusive emphasis on housing and environmental regulation. Efforts to reduce lead hazards in housing have been slow—there were an estimated 24 million houses with lead hazards in 1999 and still 21.9 million in 2019. By collapsing the concept of prevention into a single, upstream intervention, a false dichotomy was created: treat the environment or treat the child. While the shift to primary prevention was justified and much needed at the time, our abandonment of a search for treatment was not. Well-designed pragmatic trials are still needed to determine the safest and most effective protocols for lowering lead levels in children. Until then, we must apply the existing guidelines with our best clinical judgement, always keeping in mind the individual context of the child in front of us, and continue to advocate vigorously for primary prevention so that fewer children ever need face this predicament.

BACKGROUND

1990—Clinical guidance regarding the management of lead-exposed children was largely based on guidance from the CDC (1985) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (1987). These statements recommended initiating chelation therapy in children with BLLs >55 µg/dL and clinical discretion between 25 and 55 µg/dL—a range which directly reflected the CDC’s definition of an elevated BLL (≥25 µg/dL). However, by 1990, new research showed IQ loss occurred as low as 10 µg/dL, raising concerns among clinicians as to whether the current recommended thresholds for intervention were sufficiently protective.

Another controversial recommendation was that prior to chelating children with BLLs below 55 µg/dL, clinicians should use EDTA provocation tests—in which a single intravenous (IV) dose of chelator is followed by urinary lead measurement to estimate ‘chelatable lead’. Despite their widespread use, these tests had limited diagnostic value, and animal studies suggested single EDTA doses might paradoxically increase brain lead concentrations, intensifying safety concerns and confusion among clinicians.

The three primary pharmacological agents in use at the time included dimercaprol (BAL)—administered via a painful intramuscular injection in peanut oil solution; calcium disodium EDTA–administered by IV; and D-penicillamine—an orally administered off-label drug approved for Wilson Disease but found to be somewhat effective at increasing urinary lead excretion. Each of the drugs in use carried unique risks, which were gradually coming to light through emerging studies and clinical experience. The 1985 CDC statement identified succimer (DMSA; dimercaptosuccinic acid) as a promising new, but unapproved, oral chelator.

In light of the disarray and lack of consensus among clinicians, in 1990, the Health Resources and Services Administration funded a national survey to determine current chelation practices being used at U.S. academic hospitals. The survey revealed widespread variability in treatment thresholds at levels as low as 20 µg/dL. Succimer, the oral compound mentioned in the 1985 CDC statement, was utilized by only one clinic participating in a special project as it awaited FDA approval.

Bock Pharma had submitted succimer for orphan drug designation in 1984, under the recently passed Orphan Drug Act (1983), and by 1990 preliminary studies suggested succimer was safer, more effective, and easier to administer than the other chelators in clinical use.

1991

Starting January 1st, 1991, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) came into effect. This meant that if a manufacturer wanted Medicaid to cover its outpatient drugs, the manufacturer would later “true up” the price by sending Medicaid a rebate check tied to how much Medicaid used the drug. Under the new law, state Medicaid programs were legally required to cover any FDA-approved drug if a manufacturer signed a rebate agreement. Most importantly, the law mandated coverage for all “medically accepted indications,” which included off-label uses supported by major medical compendia.

On January 30th, 1991, the FDA granted final marketing approval of succimer as an orphan drug for treatment of lead poisoning in children, specifically children with BLLs >45 µg/dL. McNeil Pharmaceuticals, who would market the drug, was given seven years of market exclusivity. Orphan drugs carried numerous incentives and benefits for pharmaceutical companies, and succimer’s development was largely subsidized by federal grants. To qualify as an orphan, the drug must be indicated for less than 200,000 patients. It remains unclear how the 45 µg/dL cutoff was selected. Clinical trials submitted to the FDA included children with BLLs as low as 30 µg/dL. However, ensuring the treated population included no more than 200,000 patients would have been a requirement for final FDA approval as an orphan drug. Regardless, succimer was expected to be used off-label to chelate children at much lower BLLs.

Later that year, in October 1991, the CDC released their long overdue guidance update: “Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children.” The statement included three conflicting recommendations that:

i. lowered the hard line for chelation from 55 to 45 µg/dL, aligning clinical guidance with the FDA-approved indication for succimer. Critically, the guideline allowed clinicians discretion on chelating patients with BLLs 20–45 µg/dL.

ii. lowered the BLL of concern to 10 µg/dL (a level shared by an estimated 1.7 million children), aligning it with evidence of neurotoxicity and creating new cases by definition.

iii. recommended universal lead screening for every 1- and 2-year-old child, substantially increasing the detection of these newly defined cases.

By late 1991, the federal government was caught in a fiscal trap. The CDC had mandated screening to find a massive new population of poisoned children, most of whom were low-income Medicaid patients. The MDRP had created a legal mandate for Medicaid to pay for their treatment, even if off-label. And McNeil Pharmaceuticals held a monopoly on the only safe, oral drug that made mass treatment feasible.

The only plausible way for the government to escape this ongoing fiscal obligation was to change the definition of “medical necessity.” If it could be demonstrated that chelating children in the 10–44 µg/dL range provided no long-term benefit, the state could legally justify denial of off-label treatment.

The NIEHS TLC official website acknowledged that succimer’s orphan-drug label (≥45 µg/dL) might not constrain real-world use. The

archived TLC trial website

states:

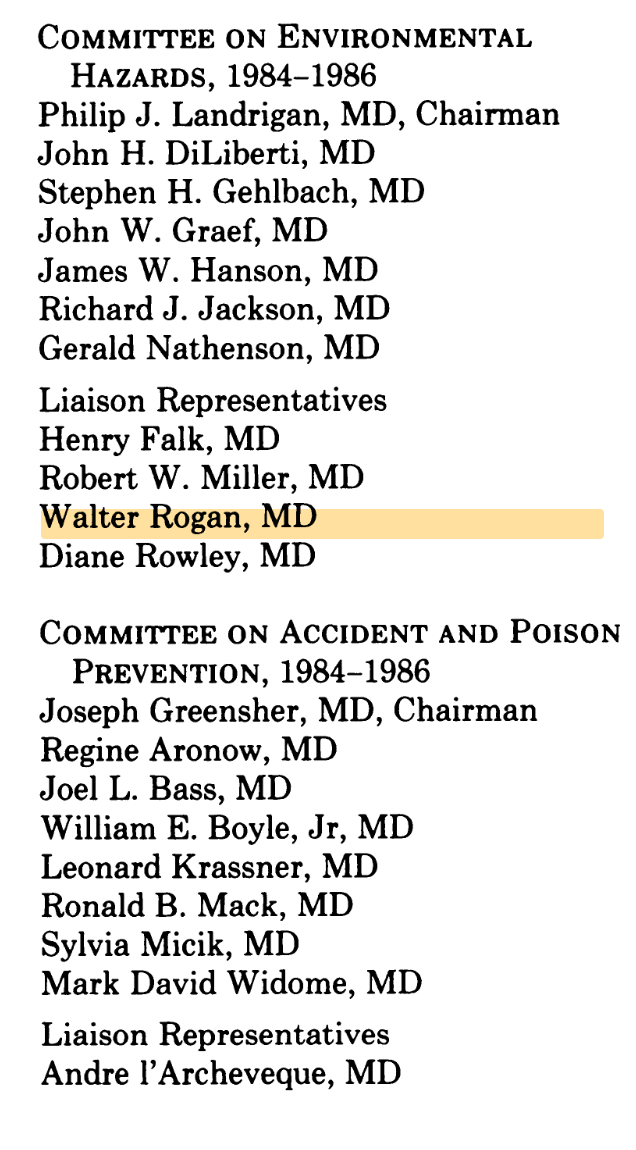

“NIEHS and its advisors, especially the American Academy of Pediatrics

Committee on Environmental Health,

believed that many children would be treated with this drug at blood leads below the labelled level, despite the fact that there was relatively little evidence of safety and no evidence of efficacy for prevention of the latent effects of lead, including developmental delay. Lowering of blood lead per se at these levels is without known clinical benefit.”

believed that many children would be treated with this drug at blood leads below the labelled level, despite the fact that there was relatively little evidence of safety and no evidence of efficacy for prevention of the latent effects of lead, including developmental delay. Lowering of blood lead per se at these levels is without known clinical benefit.”

It also foregrounded cost, without explicitly acknowledging that these costs would be borne primarily by Medicaid and other federal programs rather than by patients.

“NIEHS believed that a formal trial of succimer for the prevention of developmental delay in children was warranted. Drug therapy is costly (Chemet® costs about $300/course, most children need multiple courses over months), potentially hazardous, and would be given to asymptomatic children. Effective, simple intervention to regain lost IQ points, however, would be useful in these children and be very cost-effective in the long run. Primary prevention, i.e., prevention of exposure, is perhaps another generation away for millions of children. Good data on which to base therapy were necessary. McNeil (the pharmaceuticals company) was interested only in further studies showing that Chemet reduced blood lead, and had no plans to test the ability of the drug to prevent developmental delay.”

2001

NIEHS Director Kenneth Olden, Ph.D. said:

“For more than twenty years, NIEHS has sponsored much of the research showing that lead at these levels was harmful to children's brain function, and that succimer lowered blood lead. We had hopes that the treatment would prevent or reduce lead-induced damage in these children, who are mostly poor, African-American, and living in deteriorated housing in big cities. The results of the trial show clearly that treatment after the fact does not undo the damage among 5 year olds. We must prevent these children from being exposed in the first place.” (NIEHS Newsroom — May 9, 2001)

2016

Dr. Rogan’s NIEHS oral history described the TLC trial as a success:

“We went to where you might imagine we went. Where was the other centers? Philly, Newark, Baltimore, and Cincinnati. We followed 780 kids, half of whom had gotten Succimer, half of whom got placebo... We lowered their blood leads pretty dramatically, and we changed their IQs not at all.”

“That study ended drug treatment, which had been being promoted as something that you ought to do to these kids. It also stopped the idea of what we call secondary prevention... and moved the attention back to primary prevention, not letting them get exposed to lead in the first place.”

This wasn't framed as a disappointment, it was framed as a contribution. It moved the attention back to primary prevention. But primary prevention (removing lead from housing, environment) requires massive public investment, and is contingent on federal funding, which can fluctuate every 4 years. What actually happened was that the TLC result provided legal and medical justification for not providing treatment, while also not funding prevention at scale.

He reflected on his career:

“Nothing I've done would have been possible outside of a government agency, either NIH or CDC or EPA... My career has been very much a government scientist career.”

And Dr. Rogan was right. As lawsuits were filed throughout the 2000s against Kennedy Krieger Institute and John Hopkins—in charge of the Baltimore Clinical site—NIEHS and Dr. Rogan got away with no repercussions. NIEHS appears to have been effectively litigation-proof due to federal sovereign immunity, FTCA procedural requirements, contract structures that offloaded liability-creating activities to state-funded components, and a steering committee structure that made federal control appear "collaborative" rather than directive.